By: Marianne O, CFA, Co-Founder & Partner, and Portfolio Manager

Lumen Global Investments

100 Women in Finance

Chair, Peer Engagement, Northern California Chapter; Education Committee Member; Co-Founder, FundWomen Conference, America Co-Lead and Global Committee Member

Recently I wrote an article on Medium published via The Hub Publication on gender equality. I reviewed some interesting history and country models and would like to share them here. I would appreciate it if you read till the end as I plead some actions.

As a non-white senior female in investment and finance working most of my life in the United States, I have often come across dismal statistics comparing women CEOs vs. men, VC-funded women entrepreneurs vs. men, female investment managers vs. males, etc.

In almost all cases, the female ratio in senior leadership positions is in the single digit despite women being over 40% of the total labour workforce. The statistics for women of color are even more depressing, often in the low single digits.

In my case and many female peers, we are the only woman in the conference room, sometimes mistaken as secretaries who pour tea and coffee.

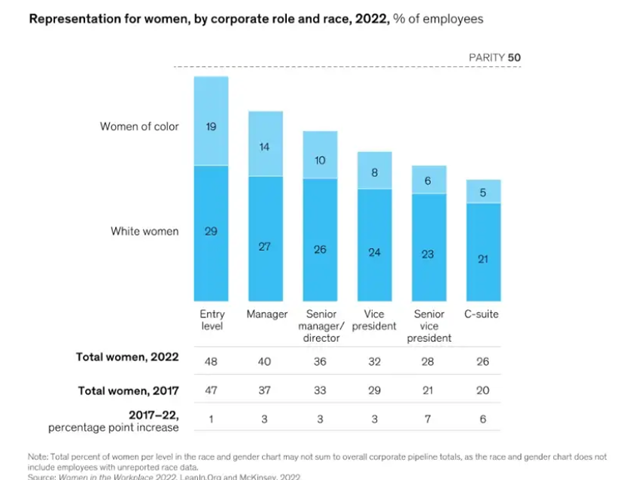

Take a look at McKinsey’s findings in Women in the Workplace 2022. Women of color comprise only 5% of C-Suite in corporate America, while white women represent 21%. From entry-level to senior manager/director level, the percentage of females dropped from 48% to 36%.

Source: McKinsey, Women in Workplace, 2022, Corporate America

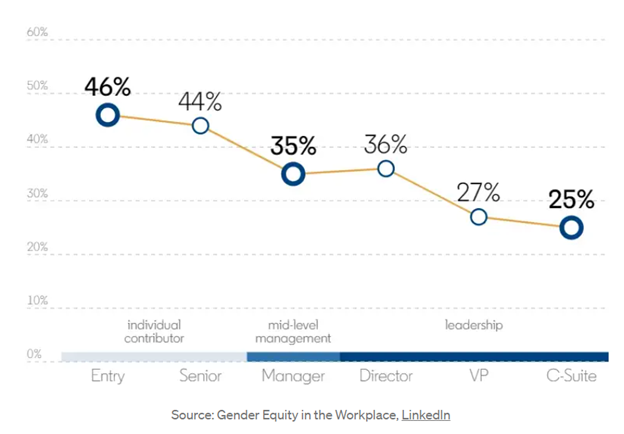

This is not just an American problem but a global issue, according to LinkedIn.

Women already face barriers at the Manager level.

Globally, women hold less than one-third of leadership positions.

LSE in the U.K. echoed:

Women make up only 6% of CEOs of FTSE 100 companies and 35% of civil service permanent secretaries — yet none of these are women of colour.

41% of women provide care for children, grandchildren, older people, or people with a disability compared to 25% of men.

Why are Senior Women Leaving their Jobs Quicker than their Male Counterparts?

The number one reason cited by McKinsey: women leaders want to advance, but they face stronger headwinds than men.

Women leaders are as likely as men at their level to want to be promoted and aspire to senior-level roles. In many companies, however, they experience microaggressions that undermine their authority and signal that it will be harder for them to advance. For example, they are far more likely than men in leadership to have colleagues imply that they aren’t qualified for their jobs. And women leaders are twice as likely as men leaders to be mistaken for someone more junior. Women leaders are also more likely to report that personal characteristics, such as their gender or being a parent, have played a role in them being denied or passed over for a raise, promotion, or chance to get ahead.

Want more statistics? From LinkedIn:

Comparing the global average for men and women in 2021, men were 33% more likely to receive an internal leadership promotion than women. In countries like the Netherlands and Spain, men are 69% and 65% more likely to get promoted internally.

New Trends Amongst these Systemic Issues

(1) According to the World Economic Forum, female founders are rising at a faster rate than male founders globally during the Pandemic, suggesting women are creating more opportunities for themselves, likely because of the need for more flexibility in juggling between personal and professional opportunities.

(2) Overall, the trend of women being hired into leadership positions has increased, rising from 35% in 2019 to 37% in 2021.

Systemic issues require systemic responses. Government and private businesses have to work together.

Let’s step back into history to look at the tiny city of Hong Kong. This fishing village has become today’s international financial hub, where women’s labor participation rate has risen to 54% by 2021.

An Unexpected History Lesson

Recently, I strolled into Tai Kwun in Hong Kong, a heritage reuse project comprising the former Central Police Station, the Former Central Magistracy, and the Victoria Prison, where they were showing an exhibit of “Gender & Space,” an illumination of the quest for gender equality in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong in the late 1800s was an entrepot, handling around 40% of all China’s trade.

Its population growth was fuelled by foreigners from different parts of the world and an influx of immigrants from Mainland China looking for economic and trading opportunities.

A significant influx of men, unaccompanied by the women from their homes, created a huge imbalance for women in marriage, concubines, prostitutes, and domestic servitude abroad.

Charles May, the first police magistrate in Hong Kong, estimated in the 1870s, only one out of six Chinese women in Hong Kong were either married or concubines, implying the rest were prostitutes, courtesans, or “protected women.” These troubling statistics likely excluded the indigenous women living in rural areas.

As Hong Kong continued to thrive as an entrepot, missionary bodies increasingly provided orphanages and learning to the destitute, abandoned, and trafficked girls while spreading religion. Convent and Baptist Schools were amongst the earliest girls’ schools. The Hong Kong government also developed public education, creating the Central School for Girls in 1890.

By 1971, the Hong Kong government established a 6-year free (later extended to 9-year) basic and universal education for all students, raising the enrollment rate of girls dramatically.

Education is the most important policy in both the public and private sectors to empower women to realize and develop their personal capabilities and full potential.

Nevertheless, we need more than just education for younger females to thrive equally with their male counterparts.

Target Policies to Achieve Gender Equality — Secrets from the Nordic Countries

Iceland tops the World Economic Forum Gender Equality ranking, closing over 90% of its gender gap, an honor it holds for the 12th year.

Next comes Finland, Norway, New Zealand, and Sweden.

What is the secret of the Nordic model when almost 75% of working-age women are part of the paid labour force?

Yes, they benefit from a well-established welfare state, but what are the specific policies to support gender equality in the work environment, in public office, and at home?

Here is a summary:

Iceland has had a history of political feminism and female empowerment since the 1970s, boasting many female role models. Men and women both have 90 days of parental leave, sharing the same burden of childrearing.

Finland’s gender equality principle has been enshrined in legislation as clearly expressed in the 1995 Act on Equality between Women and Men.

Norway has legislated a gender quota — both country’s parliament and business boards need to have 40% of female representation. Since 2013, men and women have had 14 weeks of parental leave.

Sweden, apart from boasting the most generous parental leave policy (after childbirth) of 16 months shared between both genders, the parliament uses voluntary party quotas resulting in 47% of women representation.

Closing Thoughts

Let’s end with the conclusion from the World Development Report of 2012 that pleads the case why gender equality is smart economics:

…gender equality is not only good for women. The economy has better opportunities to grow and is more resilient to crises if women and men have equal rights. Discriminatory laws and legal inequality leave the full economic potential of our global and national economies untapped. No country can achieve its full potential without the equal economic participation of women and men.

Consider three women in your life you can help raise in the coming year.

We don’t necessarily need another 132 years to close the global gender gap. We can each play a part in lessening the gender gap.

Thank you for reading!

The original article was published on December 10, 2022, on Medium.